We’re going to talk about Cual Guerra? If you have a personal experience you want to tell us, you can do that. It does not necessarily have to be your own personal experience. It can be the experience that your family told you about or that has been a consequence for the society. And if you want to make comments about the book you can also do that.

Student: I read the part about Víctor. And it is very interesting to be living with B., because he is someone who lived the experience first hand. And when I see him I think about all the things happened to him.

Well, with B, it is evident that he bears the scars that make him the person he is today. That is, he is obviously a person who suffers from something we were discussing the other day: post-traumatic stress disorder.. I don’t know… traumas. About the mind. But, in spite of that, it is really gratifying to see him in his daily life, trying to enjoy life after what happened. For me, that is one of the nicest things in the book.

Have you talked about your experiences with anyone before today?

Miguel: I have a comment about what I think about you as an author who writes in English. I think the book would be different if it were written by a Guatemalan author. For example, the book by Father Falla, Masacres en la selva, Tibuk, El verde púrpura, En Guatemala los héroes tienen quince años, La hija del puma, Resarcimiento y paz, Los héroes están bajo la tierra. These six books is very important. These Guatemalan authors of these six books have changed my life already.

Miguel: I have a comment about what I think about you as an author who writes in English. I think the book would be different if it were written by a Guatemalan author. For example, the book by Father Falla, Masacres en la selva, Tibuk, El verde púrpura, En Guatemala los héroes tienen quince años, La hija del puma, Resarcimiento y paz, Los héroes están bajo la tierra. These six books is very important. These Guatemalan authors of these six books have changed my life already.

That was one of the reasons that I was not sure that I was the right person to writes this book. Cual Guerra? not about me, it is the words of the people about their own experiences, in their own words. So it was more that I was a conduit for the stories. But read the book and see if you agree.

Miguel: I have more to say. Congratulations on your book. I hope that it will travel to many other countries, for example, the United States, Europe, the other countries, and the world, for this is a history of Guatemala, one history of my people, my country. I think it is very important for this is the consequence of this war that continues to effect Guatemalan society. These consequences of the war, the past, continue today. I think your book is very important, one more book, for us and our friends.

I see this book as the first step, and the next step is for you to write your own book if you want to.

Brenda: I agree, the best would be that the indigenous people themselves who lived this experience first-hand are the ones who do the writing… I include myself. I don’t know much because of my age, I’m too young and didn’t live that, but I really agree that it should be the real population, the ones who did live it, who write it, because in all this I understand two parts were involved, the people were divided in two groups. Now books are being written, but some leave things out, and don’t write what really happened. And I’m telling you this because this last semester I did my field practice at the Military Hospital and what they tell about what happened is different. They live in their own world and see things differently.

Brenda: I agree, the best would be that the indigenous people themselves who lived this experience first-hand are the ones who do the writing… I include myself. I don’t know much because of my age, I’m too young and didn’t live that, but I really agree that it should be the real population, the ones who did live it, who write it, because in all this I understand two parts were involved, the people were divided in two groups. Now books are being written, but some leave things out, and don’t write what really happened. And I’m telling you this because this last semester I did my field practice at the Military Hospital and what they tell about what happened is different. They live in their own world and see things differently.

Maria: Regarding writing our own book, I think that… well, at least on my family’s part, I had the personal experience I told Laurie about. But my family barely touches the subject. Well, in the past many women got involved, cousins, uncles, aunts. Maybe now writing a book can be considered because I know many people who have that intention. For example, Eliseo; for example, B. When they have the capability to write a book, I’m sure they will. The problem in the past is that we were afraid of saying things. And, in the case of my family, they are still afraid. For example, my mother doesn’t talk about these things, my aunts don’t talk about these things. In fact, they don’t know I told part of the story of my family, but it was my story, it is personal, then I told what I lived, but they don’t say anything.

Then we also need to consider that in my family some people didn’t go to school, some started school, but schools were burned down, they didn’t attend anymore. Thus it is very difficult for many people to even participate in writing a book or give us their testimonies. But I trust that now our generation, I really think so, many things are being said, people are less afraid. One feels more freedom to tell what they went through. Then, in the future there will surely be more books.

And Laurie, many thanks, really, because seriously I only spoke about all this with my mother when I was 11 years old and after that I never said anything again. Actually, I did write about it. In fact, in my computer I have the approximately 5,000 pages but, really, I had never thought about it. I think it’s the same for all of us. Then, Laurie, many thanks, really. I think this was a motivation for us to say “some day I will write my story”.

How do you think your families would feel if they read these stories in the book? Many people’s names are not the real names in the book. Most people’s names are changed. But some of yours were not changed if you wanted to use your real name.

Maria: Well, the only person that I’ve talked about this with is my sister. My sister is two years younger than me, and she remembers fewer things. She has not faced the context that indigenous people live here in Guatemala City and the environment, the social pressure there is in university, because she lives in Quiché. In a way, she is indifferent to this but, if my mother finds out, she will get scared. She would really get scared. I have aunts that even talk in hushed voices when we are in our own houses, as if suddenly we could be overheard.

Maria: Well, the only person that I’ve talked about this with is my sister. My sister is two years younger than me, and she remembers fewer things. She has not faced the context that indigenous people live here in Guatemala City and the environment, the social pressure there is in university, because she lives in Quiché. In a way, she is indifferent to this but, if my mother finds out, she will get scared. She would really get scared. I have aunts that even talk in hushed voices when we are in our own houses, as if suddenly we could be overheard.

But, I don’t think I will have a problem because of this. That’s why I didn’t want to give my full name, but only used “María” instead because, well, the experience is personal anyway, so I didn’t involve my family much, so I don’t think it would affect them much.

Just one more thing. When I gave my testimony, there were like three or four people… I hadn’t heard the testimony of the others until now. Then, this experience was traumatic for me. In fact, it didn’t let me fully live my childhood. That is, I was always affected by this psychological damage. Well, as a matter of fact, I needed psychological help when I was a teenager, I was young and all that. I never imagined that several people in the Fundación had stories even more traumatic than mine. I felt really bad, really, and I remembered all that, right? It hurts a lot. [Sobbing] But learning about the stories of the others made me feel better. Now I feel better. It made me feel better, it made me feel like a complete person because I realized many people had suffered much more than I did. It made me stronger, it encouraged me to go on, because I really felt bad, sometimes I even went through something like an existential crisis, because this was always on my mind. That is, they are things that are really hard to assimilate, even when you are a child or a teenager, but learning about the stories of the others made me feel, not good, but comfortable with my life and gave me the desire to go on.

Student: I want to add something. What Maria says is indeed true. In the towns fear to talk still persists and talking in hushed voices about those things still exists. For example, in my town, because as a child I didn’t know anything about it neither did our parents tell us about it, until we started studying and they talked about it. Currently it still brings consequences, because I remember about four years ago two boys were killed over there in my town. They were hung and their bodies turned up in the shore of the lake, but they were the grandsons of those who supposedly joined the military, they were their accomplices. And people are still angry, what happened still hurts them, and they still think about revenge. This still persists. And when they speak, when these boys died, they said “what happens is…”, in a hushed voice as if whispering or gossiping, almost like hiding, they said it, “what happens is that those people deserves that because they did such and such in the past”, but they didn’t say it out in public, but rather… I was among the adults and they talked like this among themselves, but very softly. So, it is true that fear still exists and consequences and pain still exist and they still think about taking revenge regarding that situation. That is, nothing has been forgotten, because it was really painful.

Student: Yes, the thing is, I was telling Laurie that something particular had happened in my family. In my mother’s case, she was with the guerrilla; and in my father’s case, he was with the army. And, well, in fact, some were known, but…

Student: Then… in fact, some of us were… my grandmother lived one block away and my aunt one block away. My aunt’s house served as a buzón {mailbox}. That is, a mailbox is where people leave food and later the guerrilla comes and takes it to the camp. And my uncles were aware of that, but never said a thing, and they were military. One of my father’s nephews was also a soldier. Then, well, I didn’t have… it was the normal relationship between uncle and nephew, but after the incident when those men were assassinated, of what I saw, I could see them wearing uniforms. I was a child, six, seven, eight years old. I was a child, but I hated them, then, the same with my cousin and, in fact, when they were killed , because one of them was killed. I don’t know in what zone here in the city, but I was glad when he was killed. Then, one realizes of what kind of feelings one is dealing with, that is, being glad because someone was killed, because I had it in my mind, I remembered it all and, in fact, until today, this cousin who was part of the army also lives in the US for the past six or seven years, but I could not stand him. I could not stand him. He came on one occasion and, in fact, I don’t like him. But it is not him, it’s his past. Then, one lives with those inner resentments that are difficult to handle.

So, even in the same family, people are divided against each other?

Student: But, to clarify. Before, for example, my uncles, they were part of the army because they were first snatched when they were young. They were snatched, they were taken away…

And in the end they got used to it. In the end they got used to it and in a way they made a career in the army, because one of my uncles achieved a high rank, I don’t remember, but it was a high rank. But in the beginning, he was snatched and taken away. Some managed to escape. And since they were well paid, supposedly, in those times. They snatched the boys at a young age.

How old were they when they were snatched?

Student: When they were snatched they were around 17 to 20 years old.

There is a story in the book called “Porfirio’s war”. Porfirio told me a story about boys being snatched from his school when they were 14 and 15 years old. They were teenagers and they were forced into the military. And then forced to do terrible things as soldiers. And once they were in the military, they had to do what they were ordered to do or they’d be killed. Is that true?

Student: Yes. That’s true. They were victims, too.

Manuel C.: I wanted to say something. When you first asked what are we going to do with our book, in my case, my book is a gift for my father, because my father is the only person in my family who told me about that. And I think that, as Maria said, her sister is just two years younger then her. That is my case too. I am the youngest of my family and I don’t know what was happening and nobody say, nobody tell and I don’t know.

Manuel C.: I wanted to say something. When you first asked what are we going to do with our book, in my case, my book is a gift for my father, because my father is the only person in my family who told me about that. And I think that, as Maria said, her sister is just two years younger then her. That is my case too. I am the youngest of my family and I don’t know what was happening and nobody say, nobody tell and I don’t know.

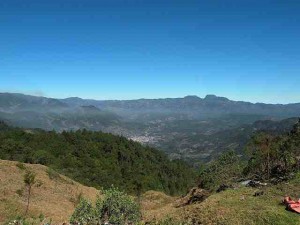

But my parents immigrated to Guatemala City, because Quiché is not a good place to live, and they took us to Guatemala City. I was born in Guatemala City. In fact, when I was two years old, we came back to Chichicastenango. That’s my case. One more thing, I think that the youngest generation don’t know about this. And in my case too. When I was younger, my mother said… my mother is the person in the family, maybe, who is more affected by this… now she discriminate against the ladinos because she thinks that all the people are the same. She thinks they are all bad.

That’s one of the reasons that she discriminates against other people, because discrimination has many aspects. Ladinos can discriminate against Maya, and Maya can discriminate against other people. So, when I was younger, I said: “Hey, but all of us are the same.” My little friends were Maya, ladinos, whatever. And then I said: “No, all of us are the same”, but reading about the history, listening a little bit of what they said, now I can understand why they feel that way. The young people who say the same that I did when I was young, it’s is because they don’t know. They simply don’t know what happened. That’s the reason.

Student: And, I think that really, I want to communicate this to you, that we have to be aware that this is happening to us. Most of the people who are here, most of us who are here, live in Guatemala City and it would be like living a fantasy if we believe that this didn’t affect us and there are no consequences. I personally think that there are also problems, that is, walking in the city is not the same as walking in our towns, with a majority of indigenous people, one can feel awkward. One feels discriminated against. In Guatemala City it is even worse. I really believe that it would be a real pity if young people do not understand that what happened is not in the past, we still have consequences and discrimination is the most evident. I think this is what happens. We have to open our eyes and realize it. I say that things are still real today.

Until 1996, with the signing of the Peace Accords and, well, since then we are noticing that small changes are really taking place. There are little changes. In fact, we are living one of those changes.

Brenda: What could we do so that these changes that have occurred, the small changes that have occurred regarding discrimination keep getting better. That is, the further eradication of discrimination.

Johanna: First, to comment about the book. I read a little and it was a good idea, a very good idea, to not change anything and to have written exactly what people said and then to make your comments, because it captures what they really experienced. And there are books that.–Miguel mentioned some–that tell the truth. I didn’t live any of it, but my parents did tell me some things, but not much because they don’t want to remember and because they know there is not as much problem as there used to be. It was worse in Alta Verapaz and Baja Verapaz, the most affected was Baja Verapaz, in Rabinal, .. most people from Rabinal moved to the US, because there was a lot of trouble there. In my case, in San Cristóbal, the most affected were those living in the villages. All the boys were recruited. They didn’t ask them, they only looked to see if there was a boy or a man and they took them. They didn’t ask them if they wanted to be with the military or with the guerrilla, they were forced to join. They didn’t have any intention of killing. Their intention was not to harm, but they were forced, many of them, and seeing that, other people also decided to join the guerrilla because they had no other choice, they had to defend themselves from so much harm. The way they tell it, it was difficult. And it is a very good idea to write a book about the people who did live it or ask older people to tell their experiences, because there are some who are willing to tell their stories and they are the ones who lived it more intensely. And about how to stop, or diminish discrimination, I think the fact of not feeling bad about wearing the traje with which we represent our town. In University, there in Cobán, very few women wear the traje and everybody seems surprised to see someone wearing it and I think we shouldn’t be… we should be proud of what we are and we shouldn’t discriminate against others either, because then we would be contributing to…maintaining a vicious cycle.

Johanna: First, to comment about the book. I read a little and it was a good idea, a very good idea, to not change anything and to have written exactly what people said and then to make your comments, because it captures what they really experienced. And there are books that.–Miguel mentioned some–that tell the truth. I didn’t live any of it, but my parents did tell me some things, but not much because they don’t want to remember and because they know there is not as much problem as there used to be. It was worse in Alta Verapaz and Baja Verapaz, the most affected was Baja Verapaz, in Rabinal, .. most people from Rabinal moved to the US, because there was a lot of trouble there. In my case, in San Cristóbal, the most affected were those living in the villages. All the boys were recruited. They didn’t ask them, they only looked to see if there was a boy or a man and they took them. They didn’t ask them if they wanted to be with the military or with the guerrilla, they were forced to join. They didn’t have any intention of killing. Their intention was not to harm, but they were forced, many of them, and seeing that, other people also decided to join the guerrilla because they had no other choice, they had to defend themselves from so much harm. The way they tell it, it was difficult. And it is a very good idea to write a book about the people who did live it or ask older people to tell their experiences, because there are some who are willing to tell their stories and they are the ones who lived it more intensely. And about how to stop, or diminish discrimination, I think the fact of not feeling bad about wearing the traje with which we represent our town. In University, there in Cobán, very few women wear the traje and everybody seems surprised to see someone wearing it and I think we shouldn’t be… we should be proud of what we are and we shouldn’t discriminate against others either, because then we would be contributing to…maintaining a vicious cycle.

Yes, because the fact that we only think of ourselves means that we are also discriminating. That’s all.

A.G.: I didn’t live any personal experience, because I think I was not born yet back then, but what Brenda and Maria said about our grandparents still not wanting to talk about it is true, because in my family my two uncles were recruited by the army, my mother’s brothers, but they escaped. The thing is that, when they went to the villages, I think they killed people, but… well, in fact, one of my uncles seems to hate all the soldiers, although he was part of it. I think they still keep silent about it and, in fact, in my house, although my uncles and my grandfather, my mother’s father, lived it, they never talked with us about it. Now, I had the opportunity to meet in a boarding school in Chimaltenango several compañeros who were Mexican repatriates after the Peace Accords. There is something very important is to realize that, like in the case of my friends, I know these have been or were very difficult experiences because many of them were orphans and lived these experiences first hand when they were kids. Some were saved by their grandmothers or by people who knew them.

Then, something very important is that, in spite of the scars they have and in spite of how hard their lives have been, having to leave their country or living in fear, they have been really strong people and worthy of admiration because, like Maria, they have made the best of themselves. Perhaps it has been difficult, emotionally and in other ways, but they go on with their lives and I think they are incredible people, not only young people, but also people who lived in those times, like our grandparents or the parents of some of us. Then, I think it is worthy of admiration the fact that they managed to overcome the barriers and have studied and have developed personally regardless of their experiences and the conditions of some families in their towns after all that happened. And I think that yes, the consequences of what happened are evident in the fear some people experience or in the feelings they keep inside that may well be resentments, feelings that are hurting these people because of the unpleasant, really painful experiences they have gone through. That’s all.

Manuel C.: I am looking for my spiritual guide. Because I know that I need some help, maybe not directly, but I am a consequence too…

When do the consequences end? And how does one stop it?

Manuel C.: I think never. We have to work to stop that and to do the right things at the right time.

Brenda: But I think that there will always be some resentments because, whether we want or not, those who talk tell about it to their children, to their grandchildren, then there are others who do not talk. And, for example, in my case, although I didn’t live it, but they did tell me and, when I listen, I feel that people, our people, suffered a lot. So, I don’t know, this resentment comes to me from nowhere, even though I don’t know if it’s good or bad, but what my people went through hurts me and yes, really, and I’m being honest, I don’t like soldiers, even when I work there. Yes, I still work with them.

Miguel: I have an antimilitary mentality. That is, I could never be part or vote for a military person. I couldn’t.

The experience of the community, the experience of the guerrilla and the experience of the army one way or the other, they are three totally different points of view. Totally different. And if you realize, the military movement originated from the guerrilla movement. If you take a look at history, compare books and documents, the guerrilla movement is clearly military. And comparing military life with community life, you reach a point where you say, in my case, now Maria closed a circle that I had almost forgotten about, because sometimes it is hard to acknowledge that one, due to some particular things in my life I decided to study nutrition, because I felt “well, either I do something or die trying”, for my society, for my town. But let’s leave it at that, because there are things in your past that you need to erase, you need to say… well, to replace what one way or the other your past did to your own town.

Then, sometimes it is different, right this would take all night to tell. Because you and your family could have lived with a military mind, you could have lived in the community environment or you could have lived the case of the guerrilla… or like some particular families who lived the three cases, who participated in both. Then, it depends, it depends on where did you live and how have you cleaned your thoughts and… well, those are the three points of view. Now, what can I do for myself, because in my case, I love my grandmother because I know why she is here, I know why she has me, which sometimes is part of talking with your family, talking with your family is knowing your past, because you know why you are here at this moment, why you are studying, where you live, why you are here, why not from there, what is your last name, what your last name means, what your second last name means,why you were called like that. You know all your past when you talk with your family. It is very complex, but it is part of our history, part of what we will live with all our lives and it is your decision what you will do next: either be a better person and contribute to make a better society or to go backwards. It is a point where you decide to move forward or to go backwards or stay where you are and do nothing. That is, totally different directions and you have to make a decision of which one to take.

And congratulations, Maria. In A.G.s words: “not just anybody would do it, not just anybody has the guts, there are people who have died because they spoke.” And it should be acknowledged, you and everybody else who are in the book. I’m interested in learning about the ideas of other people, I like knowing their ideas. Laurie, That’s why I asked you about Guatemalan authors and US authors, because they see us in a different way and we see ourselves in a different way.

Just a comment about what Miguel said about there being three points of view: the community, the military and the guerrilla. I think that we should understand the three points of view, because I think that throughout history people in our towns have always faced difficulties, opportunities have been denied to them. Supposedly, the guerrilla originated from a quest for equal rights and opportunities. But, as usual, people in power don’t allow others to live in a human condition, like in many communities, so it is difficult because, even when things change, they have to change much more in their roots. It is not impossible, but we have to see not only what is going on now, but also why this issue of violence came into being. Because in our towns our history has always been difficult.

Student: Since 500 years ago. Since the invasion.

Miguel: That is, our origin itself was perfect, because it was only us. The problem was Spain intruding. Because Spain brought the… That is, our origin was ideal, but Spain came and the problem started there. We were better off.

AG: We think about how how the the Maya people have suffered a lot of things, things like that problem that we lived and you are writing about.

Brenda: What opportunities or what ways or how easy it would be for us to get information about the three groups. So, I think that only through books because people don’t…

Miguel: Testimonies, but it’s not easy to have people speak that much… our people, the military and other people.

Well, that is complex, because… you know I had a friend, his name is Pichia the other was Mateo L. and they both can tell you the three points of view, because they have lived the three points of view. But it is in rare occasions that people have had the opportunity, that is, not the opportunity but that terrible experience. And talking with them… they tell you about it.

This is my opinion from the reading that I’ve done about this time. The thing is that this is a responsibility, but since Laurie is open minded, I feel that there is a kind of responsibility that also falls on the US because of the invasion, because if it weren’t for the United Fruit Company they would be fighting the guerrilla movement demands with the coffee plantations, the guerrilla movement would have never happened.

The United States, the CIA. That is, I’m telling you, it’s a subject that we as Guatemalans blame each other, but what did the foreigners do? It was part of what set it off.

Brenda: And that is precisely what Laurie was talking about yesterday, she said that the US really financed…

Yes, the Guatemalan military was trained and supported by the United States. And Israel provided the weapons like helicopters. And this is why I feel so strongly that I want this book published in the United States, because Americans don’t know about the US involvement.

One of the other volunteers is a professor at a college in the US. She has a video camera and wants to ask if you would like to give a testimonio on video, because it’s very powerful to have a face along with a story. Maybe we could take some video back to the States and develop an educational program for high school or college students to help them understand your experiences.

Miguel: It’s like, for example, the war to Iraq, which is what is currently going on is a country they are invading because of their oil. What consequences will there be in Iraq 25 or 30 years from now after the US invasion?

I want to tell you something. We are talking about this thing as this thing were in the past. This thing is not in the past. In these days, we can’t talk about openly, freely because I don’t know if they are just worries that people have, but people think yet that there are spies. That there are spies in Guatemala.

Manuel C: Yes, yes. When you invited us to participate in this, I felt a little bit of fear. Yes, I was a little scared, because I think, ok, I will do… maybe tomorrow.

Maria: I understand that this weekend you are thinking of filming everything for educational purposes, that is, testimonies of my case and the case of other students. Well, personally, honestly I’m still afraid, so I’m not sure about what I want to do, I am sure about many of my purposes, of my goals, but I wouldn’t like a video because I think that… I’m afraid of involving my family in the future, because you never know. Things are getting worse all the time all around the world, so I understand their good intention of taking it to another country and letting them know about the history, our history, our cases and all that, but I think that… well, I don’t know, I’m still afraid. I’m still afraid. I participated in the book and I’m very grateful to Laurie. Well, in fact, I only appear as María, but for reasons of security. I think we are all different, and I wouldn’t like to participate in the video.

For your family or for yourself?

Maria: Myself and my family.

Well, I think that… I’d have to think about it. That is, I’ll think about it because I need to analyze this. Why? Because I can’t involve other people. Then, well, one thing is me and another thing is my family. I don’t want to affect my family. So, you love your dear ones, some day I will have a family of my own… so…I’ll think about it.

Thank you all for your openness and honesty. I am very touched .

Miguel: And congratulations to you.